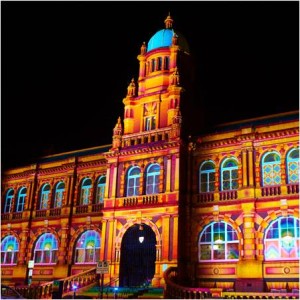

A seminar run by the Institute for Local Governance, Friday 22nd May 2015, Redcar and Cleveland College, Redcar

Producing a strategy to match the skills and needs of employers in Tees Valley with the skills and aspirations of young people is not a straight-forward issue. Much of the locally-owned institutional support for such an initiative has been eroded with the loss of once generously funded organisations such as Connexions Tees Valley, The Tees Valley Learning and Skills Council and Business Link Tees Valley.

The willingness of Tees Valley to tackle skills issues for young people is, arguably, stronger than ever through the work of its Local Enterprise Partnership, Tees Valley Unlimited, local authorities and the promise of the establishment of a Tees Valley Combined Authority to integrate effort across the areas five unitary local authorities.

This seminar aims to explore the complexities surrounding ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ issues operating in and around the Tees Valley region. Speakers have been brought together to open debate on: projected employer labour demand over the next few years; how employers’ skills needs can be met through local schools, colleges and universities; and, how the potential of young people (especially those from less advantaged backgrounds) can be harnessed.

Marshalling the aspirations and developing the employability of young people (aged 15 – 29) who have experienced significant periods of time not in employment, education or training (NEET) is a controversial and challenging area of discussion. Even when money is available to tackle the issue, solutions are often difficult to produce. Being positive about the prospects of these young people is, nevertheless, vital for the area economically and socially.

This is reflected in the Government’s recent launch of its first calls for Tees Valley projects under the 2014-2020 European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and European Social Fund (ESF). Projects are being sought to maximise SME job creation, but central to the concerns of this seminar is the Youth Employment Initiative for ESF across Tees Valley.

Shorter term initiatives, however valuable, only provide part of the solution – this seminar also aims to debate the roles of private sector, education sector and third sector organisations in tackling more widely skills challenges in Tees Valley over the next few years. The seminar will seek to engage the views and experiences of participants during the course of the event.

Speakers include: Professor Robert MacDonald, Social Futures Institute, Teesside University; Carl Ditchburn, Community Campus ‘87; John Lowther, Chair of Strategic Planning for the Board of Governors, Redcar and Cleveland College; Kate Roe, Principal, Darlington College; and, Sue Hannan, Employment and Skills Manager, Tees Valley Unlimited. The Seminar will be chaired by Professor Alan Townsend, Durham University

The seminar is free to attend. Please register your attendance via: Janet Atkinson, Institute for Local Governance, Durham University. janet.atkinson@durham.ac.uk. The Institute for Local Governance is a North East Research and Knowledge Exchange Partnership established in 2009 comprising the regions Universities, Local Authorities, Police and Fire and Rescue Services.

Tony Chapman, Professorial Fellow at St Chads, spoke to researchers in the School of Applied Social Sciences at Durham University on 3rd February on how to harness ideas and findings to shape the way policy makers make decisions. It was argued that while social scientific research was undertaken rigorously, it invariably stems from a position of ‘interest’, so there is always a risk of the accusation of bias. Consequently, researchers have to be particularly careful about how they present their findings to people of influence.

Tony Chapman, Professorial Fellow at St Chads, spoke to researchers in the School of Applied Social Sciences at Durham University on 3rd February on how to harness ideas and findings to shape the way policy makers make decisions. It was argued that while social scientific research was undertaken rigorously, it invariably stems from a position of ‘interest’, so there is always a risk of the accusation of bias. Consequently, researchers have to be particularly careful about how they present their findings to people of influence.